Anne Pöhlmann, Japanraum by Moritz Scheper

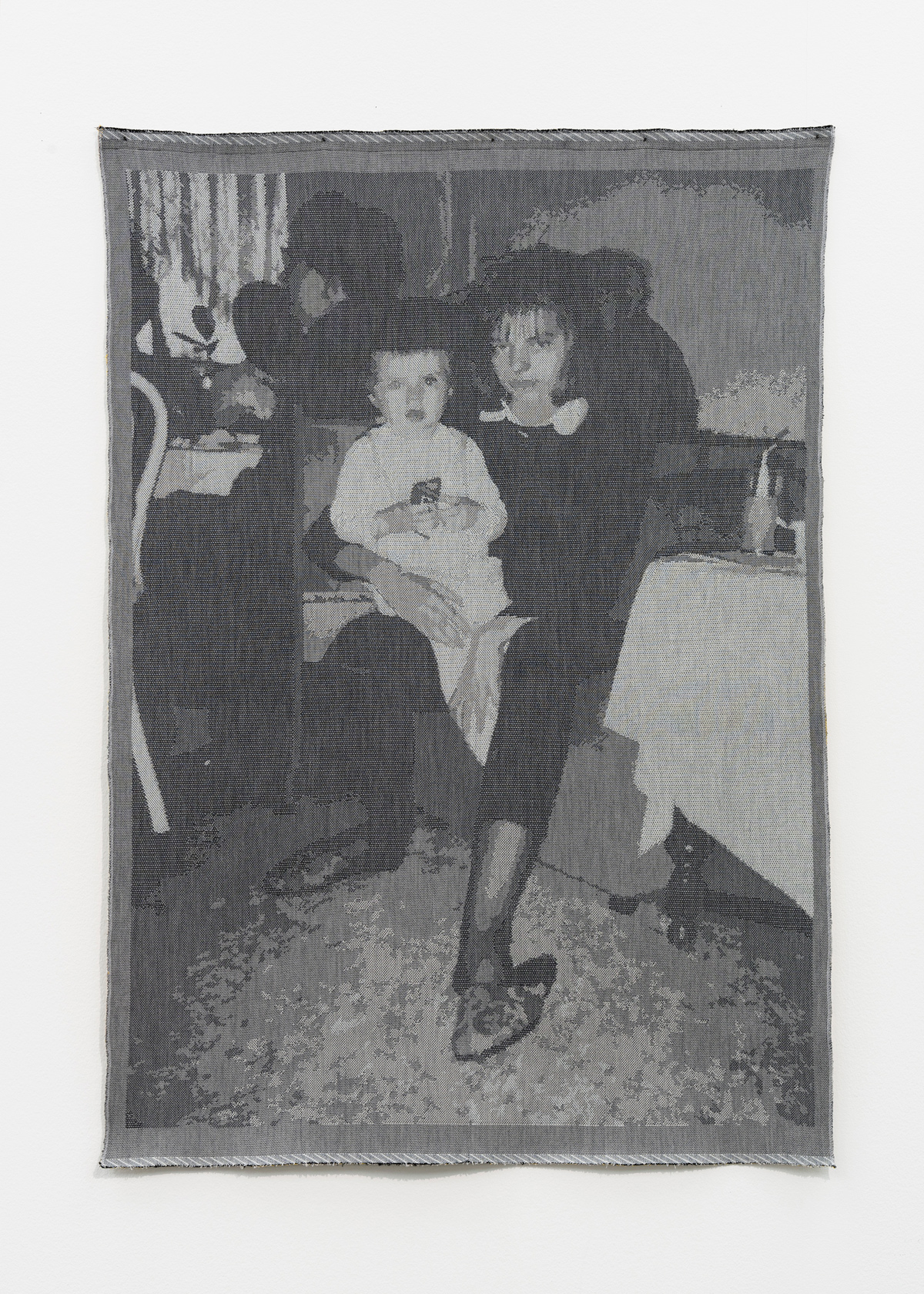

Anne Pöhlmann’s exhibition Japanraum is based on the experiences and impressions of a three-month residency in Kyoto. The resulting mixed media works are photographs printed on textiles, which were taken in Japan, and then sewn onto various other fabrics. This process leads to a space between framing and expansion of the image, while the movable materiality of the fabrics evoke a spatial three-dimensional texture in the pictures. The textile enlargement also reveals an offset between image and image carrier, and this distinction is most apparent when photography no longer takes place on paper. It is clear that digital photography, which is no longer quite new, has once again moved the photo’s location. This medium can do without material fixation; put in devices—mostly backlit— and laid out on textiles, bricks or directly on three-dimensional objects.

The mere use of a different carrier-material emphasizes Pöhlmann’s handling of her medium as an extremely contemporary one, even if older fabrics with which she partly works with do not suggest this. This is relevant to mention since the majority of her diaristic pictures were photographed with a mobile phone, which is most likely the technical equivalent closely corresponding to the spatial shift of photography. In every case, this technical framing determines the spontaneous character of the images, which do not cling to thematic complexes or motifs, but instead mark a processing of visual impressions. Ikebanas, street scenes, scenic details, brutalist buildings or rock gardens are captured. If one was to deduce an underlying theme from the pictorial content, it would probably be astonishment: the gap between everyday pragmatism in hyper-modern Japan and traditionalism with its regulated passion for detail. Pöhlmann conveys the distance between tradition and modernity through the textiles in her works, which on the one hand include high-tech products such as a perforated fabric by Raf Simons, and on the other present hand-woven silks. During her stay in Japan, the artist bought these fabrics at flea markets for very little money, as many Japanese people are presently parting with traditional textiles and garments. Pöhlmann registers this difference without commenting on it in any form. Her point of view is that of the Western outsider, aware of the limited knowledge on this completely different culture. The outsider knows that bits of cultural context are learned looking in from the outside, and because of their limited knowledge, they are not entitled to draw any conclusions. The diary-like quality of the photographs correspond to this point of view, since Pöhlmann repeatedly assumes the position of the uninitiated outsider. She does this through consciously unsystematic photographs of Japanese traditions, but above all through her images of architecture, which explicitly present an “outside”. The interior view of the Jugetsukan on the grounds of the imperial Shugakuin villa most definitely stands out among all her motifs. The photograph directly evokes another imperial building that has played a central role within the intercultural exchange between Japan and the West: the Katsura Villa, which can hardly be photographed from the inside. The popular story that architect Bruno Taut rediscovered the building for Westerners and Japanese alike is unquestionably an exaggeration. As a representative of the European avant-garde, he interpreted the villa as an early testimony to modern functionalism. This interpretation of the building situated modernist architecture as part of an old line of tradition, in which Taut mediated and intervened in a confrontational architectural battle between traditionalists and modernists. Interestingly, Pöhlmann’s project in Japan also registers a certain irreconcilability between the present and past.

Katsura is also relevant from another perspective, one which is a factor in the Western view of Japan and in contact with foreign cultures in general; here it becomes quite clear how the familiar is strongly sought and emphasized in the foreign. An exemplary example of this is photography’s role within the appropriation of Katsura, which can be seen in U.S. trained figure, Yasuhiro Ishimoto. His now iconic black-and-white photographs of the 1950s villa mainly concentrate on the interior while indulging in constructivism, which then naturally emphasized the building’s connectivity to Western modern architecture. By incorporating Katsura’s motifs into her series, Anne Pöhlmann is sensitive toward the problem of the photographic image in terms of producing and reproducing cultural stereotypes and intercultural misunderstandings. Above all, in Japanraum, Katsura and his history mark the entrance to a discursive space of intercultural contact in which self-understanding, understanding, and misunderstanding lie close together.

Translation by Jessica Gispert

Langen Foundation

Raketenstation Hombroich 1

41472 Neuss

Tel: +49 (0)2182 / 5701 – 15

Fax: +49 (0)2182 / 5701 – 10

info(at)langenfoundation.de